Northern Harrier

General Description

Formerly known as the Marsh Hawk, the Northern Harrier is a slender, medium-sized raptor with a long, barred tail and distinctive white rump. It has an owl-like facial disk that is visible at close range. Harriers are unusual in that there is a greater difference between male and female plumage than is typical of raptors. Females are brown above with varying degrees of brown and buff streaking below. Males are gray above with an unmarked lighter color below; they also have black wingtips. Juveniles are brown above and plain orange-brown below. In Eurasia, this bird is known as the 'Hen Harrier.'

Habitat

Northern Harriers are open-country birds, often seen soaring low over grassland. They also occur in farmlands, parks, and steppe habitat.

Behavior

During winter, Northern Harriers sometimes roost on the ground in groups. Harriers use their sense of hearing more than other hawks, flying low over open fields and listening for prey. In flight, they hold their wings up in a slight 'V' position.

Diet

Diet varies based on prey availability, but Northern Harriers take mostly small mammals and sometimes birds. In spring and winter, especially in the northern part of their range, they prey predominantly on voles.

Nesting

The male Northern Harrier attracts a female with a roller-coaster display flight, often performing 25 rises and falls. In Washington, these displays can be seen as early as late February. Loose colonies may form, and males may mate with up to five females in a season, although monogamy is more common. The number of females a male can support is related to the abundance of prey in the spring, which can vary greatly. The male usually starts the nest, and the female then takes over construction. They build the nest on the ground in dense clumps of vegetation. The female incubates the 4 to 6 eggs for 30 to 32 days, and broods them for two weeks after they hatch. The male provides most of the food for the female and nestlings during this period. After two weeks, the nestlings begin to walk around, and at 4 to 5 weeks, they begin to make short flights from the nest area. By 45 days, they make sustained flights. Once they can fly, the parents feed them in mid-air, passing food to the first fledgling to reach them.

Migration Status

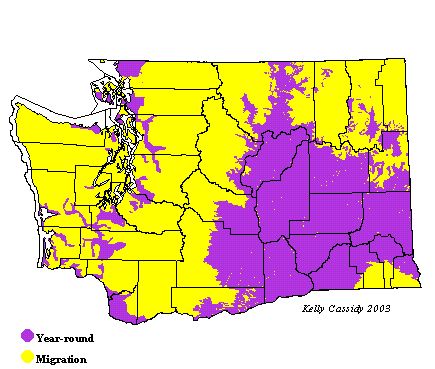

As with most species that prey heavily on voles, Northern Harriers are somewhat nomadic, and densities change with the abundance of prey. Throughout much of their range, they are long-distance migrants, wintering as far south as Panama, but they are resident in other areas, including Washington.

Conservation Status

During the middle of the 20th Century, Northern Harriers experienced declines due to pesticide use. The regulation of DDT has helped the harrier population recover, although habitat loss is still a significant threat. Many wetlands and open spaces are in danger of development or conversion to less beneficial habitat. Overgrazing also affects their habitat. Numbers have severely declined in the East due to increasing numbers of ground predators and lack of habitat. Northern Harriers are, however, fairly adaptable and generalized, and seem to be fairly stable in North America in spite of these threats. Numbers are, however, on the decline globally.

When and Where to Find in Washington

Washington has both breeding and wintering populations of Northern Harriers. Additionally, migrants occur throughout the state. In winter, they can be found in open lowlands throughout much of the state. As breeders, they are most common in eastern Washington, but also breed in the Puget Trough and on the southern outer coast.

Abundance

Abundance

| Ecoregion | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oceanic | ||||||||||||

| Pacific Northwest Coast | C | C | C | C | C | U | U | U | F | C | C | C |

| Puget Trough | F | F | F | F | U | U | U | U | F | F | F | F |

| North Cascades | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | U | U | U | R | R |

| West Cascades | F | F | F | F | U | U | U | U | F | F | F | F |

| East Cascades | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R |

| Okanogan | F | F | F | F | F | F | F | F | F | F | F | F |

| Canadian Rockies | U | U | U | U | U | U | U | U | U | U | U | U |

| Blue Mountains | U | U | U | U | U | U | U | U | U | U | U | U |

| Columbia Plateau | F | F | F | F | F | F | F | F | F | F | F | F |

Washington Range Map

North American Range Map

Family Members

OspreyPandion haliaetus

OspreyPandion haliaetus White-tailed KiteElanus leucurus

White-tailed KiteElanus leucurus Bald EagleHaliaeetus leucocephalus

Bald EagleHaliaeetus leucocephalus Northern HarrierCircus cyaneus

Northern HarrierCircus cyaneus Sharp-shinned HawkAccipiter striatus

Sharp-shinned HawkAccipiter striatus Cooper's HawkAccipiter cooperii

Cooper's HawkAccipiter cooperii Northern GoshawkAccipiter gentilis

Northern GoshawkAccipiter gentilis Red-shouldered HawkButeo lineatus

Red-shouldered HawkButeo lineatus Broad-winged HawkButeo platypterus

Broad-winged HawkButeo platypterus Swainson's HawkButeo swainsoni

Swainson's HawkButeo swainsoni Red-tailed HawkButeo jamaicensis

Red-tailed HawkButeo jamaicensis Ferruginous HawkButeo regalis

Ferruginous HawkButeo regalis Rough-legged HawkButeo lagopus

Rough-legged HawkButeo lagopus Golden EagleAquila chrysaetos

Golden EagleAquila chrysaetos